Odile Decq

ArchIdea 62 Interview, December 2020

One cannot say that the architect Odile Decq has modest ambitions. Her architecture, often folded and fragmented, is strikingly unconventional. Her Paris based architectural school, the Confluence Institute for Innovation and Creative Strategies in Architecture, challenges educational conventions. At a lecture at Harvard, a few years ago, she stated that she wanted to reintroduce architecture as a central core in the world. Very few architects would dare cherish such pretensions nowadays, let alone speak of it aloud.

In an interview via Skype she shed some light on her intentions. "When I was preparing the new school of architecture, I got into a discussion with a group of friends, most of them architects, about some fundamental questions: what do we mean by a school of architecture, what do we mean by an architectural education, and how can we better adapt architectural education to the conditions of the world today? The world has changed a lot this century, mainly because of vast expansion of computing power. Students who are now choosing to study architecture grew up in a digital world. But education at most architectural schools is still rooted in the 19th century, and sometimes in the 20th century, but certainly not in the 21st century."

"My generation was born after Second World War and was determined to change the world. It was changing already but we wanted it to change faster. However, today's youngest generation are told by their parents that the world will never be as nice as it was for them. They tend to think negatively about their future. They are concerned about issues like global warming and gender equality, but they often lack the determination or the confidence to do something about it. I want to stimulate them to have courage. That is why I tell my students that I am jealous of them: they have a century ahead of them which they can shape according to their dreams."

"The Académie des Beaux-Arts teaches that architecture is the mother of all arts, but in my opinion it is much more than that. It goes beyond designing objects, for it is also about sociology, politics, geography, economics, law etc. As architects, we are confronted with all these disciplines in every project. We need to know precisely what the conditions of a project are. We have to bring these disciplines together into a synthesis that addresses all the relevant issues. This synthesis generates an idea, and this idea is the project. The idea is more than the building, because it deals with all the scales involved from the smallest details to the urban space. That is why I consider the architectural discipline as unique. It can help a company to reorganize itself, or it can help a city to function better. It can really change the world."

Photo: Franck Juery

.jpg)

Some people say the importance of architects to the building process has declined. Can they regain their position?

"Regaining position is a question of power. But for me it is not the question that matters. Instead of gaining power, a certain attitude is required. It is about knowing who you are and how you can deal with the circumstances you are in. That comes down to finding a position in the world. You could say that we are going back to the ideals of the Seventies in our thinking. The idea of my school is that architectural students must learn who they are and what position they can take."

"First of all, there are no courses, at least not in the traditional sense. These days you don’t see the faces of students any more, just the tops of their heads. They are on their phones all the time, looking for ideas or checking on the internet if what you tell them is correct. So the question is why we, as teachers, bother to stand in front of them repeating what they can read on their phones. Students educate themselves by using their phones and their laptops. Our task is to help them to find their way and to become self-critical. This calls for a very personal approach. It is not about educating a group, but about educating them as individuals. They also learn by doing. As soon as they have a chance to build something, whatever the size, they get excited and learn much more from it than they would in a more traditional educational setting. They create something, they manipulate something with their hands, and we offer feedback. That is why you could call my school a Montessori School of architecture.

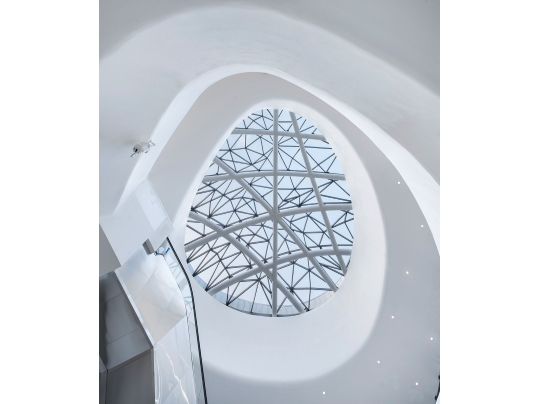

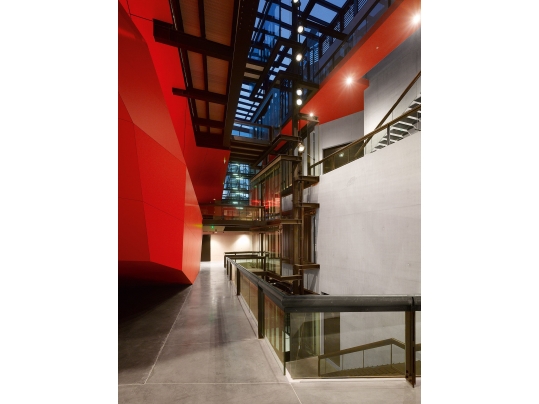

Not only in her architectural school but also in her own architecture, Odile Decq is inclined to break with conventions. It becomes clear in the way she deals with space and form: instead of taking an orthogonal, Cartesian standpoint, she folds and fragments her spaces. "I have no affinity with the neoclassicist approach that still prevails in French architecture," she explains. "Neoclassicism means that you always enter a building at the centre. From there the space reveals itself to the right and left in the same way. The spaces are essentially static as you pass from one to another. This neoclassicism is even recognizable in the buildings of Jean Nouvel: whatever the freedom of the exterior is, you enter his buildings at the centre. I don’t want to do that. I am not interested in entering into a space and being astonished by it. I always try to enter the building obliquely and then to move and travel inside it, to explore the space by a freedom of movement. When I visit a building, I love to discover step by step how the space is organized. I like to create spaces where what you see is not what is there. The building keeps on surprising you as you go deeper into it. In that sense, my architecture is baroque."

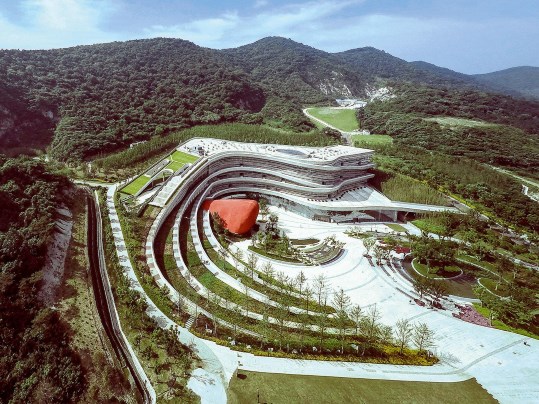

FANGSHAN TANGSHAN NATIONAL GEOPARK MUSEUM

Photos: Jinri & Zhu Jie

There seems to be a contradiction in your work, or at least a dialectic tension. On the one hand you create that freedom of movement, but on the other hand you seduce the user to go on.

"I don’t think I try to seduce the users. But I know they love to be in my buildings. I don’t usually start designing a building from the outside when I do a new project. I don’t create objects, I create spaces. Or to put it more precisely, I create ways of practising spaces, of using them. The shape of the building comes after that. Because I have my practice in France, the shape often needs to be bolder than I personally like. I have to respect the preferences of the society in which I live and work. The French usually like a building to be an object, a monolith."

However, it seems that you like to play a game of hide-and-seek in your architecture. That is how seduction works, doesn’t it?

"I don’t think I want to hide anything. But I certainly want people to be surprised and to have fun. Life is so complicated that I want them to forget about the hardship of it, and enjoy themselves when they happen to be in my buildings. I want them to feel comfortable,

not as an escape from reality, as in a dream, but to experience a suspension of time."

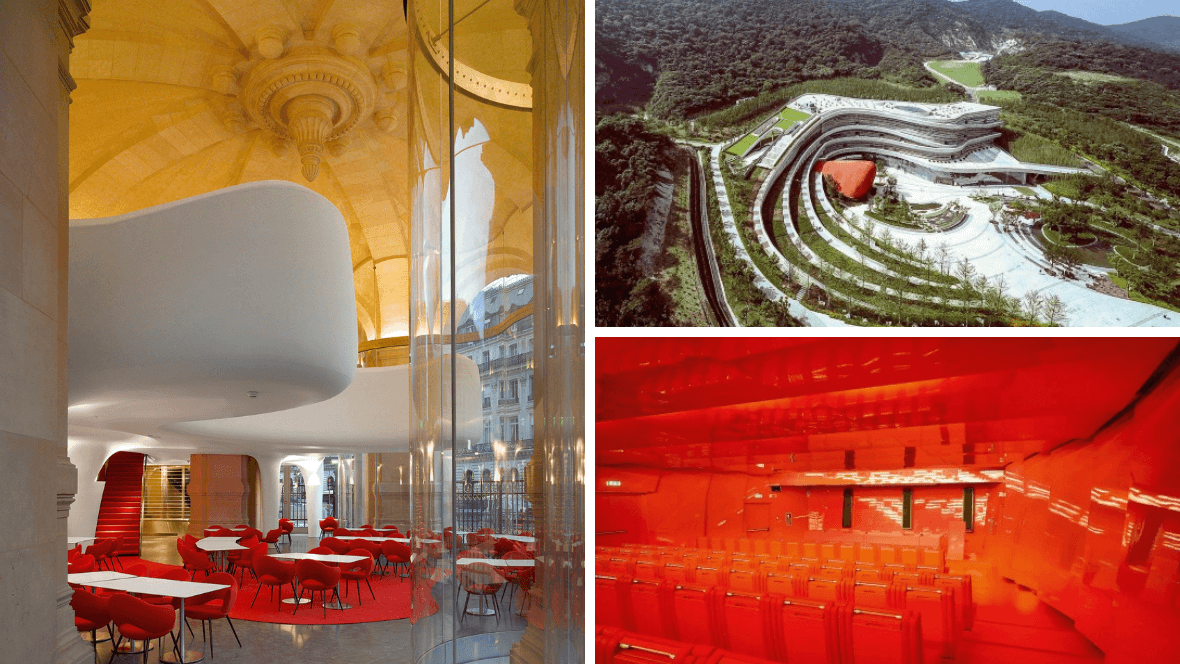

PHANTOM: RESTAURANT OF OPÉRA GARNIER : Ronald Halbe

You often use red and black in a very pronounced way, as if you want the user to take a position towards it.

"I have been trapped in black since I was young. I cannot do anything else but wear black or at least a mixture. Black is a nice, neutral colour. At the same time black, as the French artist Pierre Soulages said, is the light. It creates fantastic contrasts when you put something in front of a black wall. Red acts as a wonderful contrast to black. I don't use this contrast everywhere and when I do use it it's not always in the same way, but it is true that I am fond of applying it. When I have to name a colour I choose red first of all, because red imparts energy to a space or a building. Sometimes other people in my office propose red, but red is not obligatory. We can use other colours as well, as for instance in the renovation of the Bubble house. I am perfectly capable of playing with other colours. But they cannot be soft, they have to be bright. This is who I am. It's my character."

MACRO CONTEMPORARY ART MUSEUM Photo: Roland Halbe

"I was born a rebel. It's in my nature."

In your architecture you apply architectural elements like the window, the stairs, the ramp and the walkway in a very distinct way. To a certain extent they constitute your architecture. Can you say why they are so important to you?

"Maybe it has to do with my love for detail. I love to detail my projects very precisely. There are three phases in my projects that really excite me a lot: to develop the idea, to geometrize the design, and to detail the project at the end of the building process, which I usually do in collaboration with the contractors. Details are crucial for me because they are close to the body. The railing that you touch, the door that you pass... maybe it is exactly here, in the details, that architecture has lost its relation to humans. A lot of architects neglect the relation of architecture to the body. But I love to touch things. I appreciate the sensual quality of architecture and the texture of the material."

Wood and stone have a strong tactile quality. Although you sometimes use these natural materials, steel and glass remain your favourites. Why?

"What I like about steel is the precision that is required when applying it. You have to be precise with stone and concrete too, but with steel it is really a matter of millimetres. The calculations have to be very accurate. Glass is a challenging material because it has a lot of possibilities. You can use it in many ways and play with perception."

You started your architectural career with a fascination for high tech. Since then you have evolved to so-called soft tech. Can you explain what you mean by that?

"Soft tech is magical for me. It is sophisticated and technological, but unlike high tech it does not engage in exhibitionism. You can’t see how things are done. You don’t know how something is suspended and you don’t know how something is attached. It is basically the same game as I play with mirrors and reflections: it is not immediately clear what you actually see in front of you. Because of this perceptual confusion, users become more aware of their bodily presence."

You could characterize your architecture as restless. Is it your aim to express the restlessness of our current time?

"My architecture comes from my intuition and the way I experience a space and move in it. It is not about restlessness, but about going forward and looking what is in front of you instead of looking backwards, to the

past. But again, that is me. I am not a contemplative person. I have always been fascinated by speed and movement. For me moving and travelling are freedom. It is being alive."

Do you agree that there is a rebellious tendency in your architectural attitude?

"For sure. I rebel against the neoclassicist way of thinking in France. I rebel against the fact that I have to build boxes. I rebel against the fact that women are not sufficiently represented in architecture. I rebel against an architectural education that is not adapted to the 21st century. I rebel against a lot of different things. I was born a rebel. It is my nature."

FRAC BRETAGNE Photo: Roland Halbe

Want to read more interviews like this? ArchIdea is our bi-annual magazine that features well known and upcoming architects from all over the world alongside some of the latest projects in which our floor covering has been installed.

To start receiving your FREE copy, sign up here